Museum of Modern Art San Francisco Wall Section Museum of Modern Art San Francisco Section Drawing

Recent scholarship on Robert Rauschenberg's Collection (1954/1955) has trained a wide array of theoretical lenses on the artwork's endlessly circuitous and connotative surface, reading it variously every bit an autobiography, an embodiment of postmodern multiplicity, or a coded communiqué to Jasper Johns (b. 1930).1 Yet perhaps the well-nigh compelling story to be told about the artwork centers on the material life of the object itself, a narrative that includes Rauschenberg tussling with the implications of his own evolving artistic strategies in a significant reworking of the piece around 1955. The development of Collection from its commencement showing in belatedly 1954 (at which bespeak it was untitled)2 through its subsequent changes charts a path away from jumbled surfaces unified through monochromatic paint coverage—as seen in the Red Paintings (1953–54) and the Black paintings (1951–53)—toward a more expressive use of varied pigment colors and a freewheeling assemblage of fragments of daily life. Rauschenberg'southward evolution of the Combine—a radical form that blends painting and sculpture—took place during the development of Collection. The Combines are subdivided into "Combine paintings," which hang or orient themselves primarily against the wall, and "Combines," which comprise wall and floor components or stand fully on the floor. The starting time Combine works were Combine paintings, such as Collection and Charlene (1954).3 The present essay argues for an agreement of Drove not but as the key transitional work leading to the Combines, but also as a marker of the bespeak at which Rauschenberg began breaking down the boundaries between art, life, and society—an appointment with everyday materials and events that would come up to ascertain his oeuvre and, indeed, much of postwar fine art.

Drove, Get-go State

2. Detail of verso of Robert Rauschenberg's Drove (1954/1955) showing the abutment of two panels

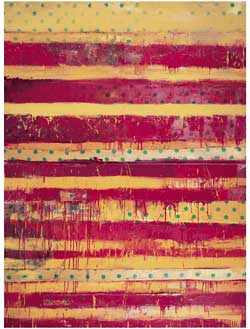

Rauschenberg began work on Collection sometime in mid-1954,4 and he synthetic it as a triptych, a format he had used previously, most notably in his 1951 White Painting [three panel]. From left to correct, Collection's three raw canvas substrates are overlaid with bright ruby, yellow, and bluish silk, respectively. The silks are at present moderately faded, merely their original intensity is still visible at their tacked edges in the console joints on the artwork's verso (fig. 2). In a 1999 interview conducted at SFMOMA, Rauschenberg described his decision to cover the canvases with the colored fabrics equally a deliberate effort to suspension away from his previous three monochromatic series (Blackness paintings, White Paintings, and Crimson Paintings). He quipped that he thought the chief colors "would scare me enough to get into color,"5 suggesting that from the very start he set out to explore new territory through the cosmos of Collection.

three. Installation view of Robert Rauschenberg's Drove (1954/1955) in Bob Rauschenberg, Charles Egan Gallery, New York, December 1954–January 1955. Photo: Robert Rauschenberg, courtesy the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

The earliest known photograph of Collection shows it at an oblique angle, hanging in a gallery context (fig. 3). Based on the physical characteristics of the room, this previously unpublished black-and-white snapshot has been identified as an installation view of the first public presentation of the artwork, the 1954–55 exhibition of Rauschenberg's Red Paintings and Combines at Charles Egan Gallery, New York.6 The bending and minor format of the photo complicate whatever detailed visual reading of Collection's surface, but side-by-side comparison with more recent photos of the artwork reveals that the creative person made major alterations after the snapshot was taken, presumably afterwards the exhibition closed.7 Accepting that this artwork was a proving ground on which the artist worked through many of the strategies that distinguish the Combines from his earlier series, what tin we acquire from the differences betwixt the early country of Collection equally seen in the Egan photo and the concluding, current state? In the Egan snapshot, much of the work's basic structure corresponds to its electric current status. The multicolored stripes across the bottom are nowadays, while the upper two-thirds is cluttered with newspaper, scraps of fabric, and thin washes and patches of paint. The small mirror is in that location, embedded just off-center and veiled with sheer material, and the scraps of wood and metal affixed to the acme edge announced just as they exercise today. In this first country, the formula of layered paint, printed matter, and fabrics resembles that of many of the Cherry Paintings and the Black paintings. Paint unifies disparate elements with color and conveys a sense of motion or activity through gestural brushwork. Even so, much of the newsprint in Collection is left uncharacteristically bare in comparison to a typical Red Painting, and the inclusion of 3-dimensional establish elements is also atypical.

In the earliest Red Paintings, such as Red Painting (1954; fig. 4),8 paint completely coats all the collage materials, and any colour variations arise primarily from the different colors and textures of the underlying surfaces.9 Untitled (Ruddy Painting) (1954; fig. 5) incorporates colors other than red through both pigment and colored textiles and begins to allow some of the disparate elements to milk shake loose from complete integration with the ruby surface, notably the striped fabrics beyond the superlative and the lacy gold textile at lower right. Nevertheless, the latter work nonetheless is overwhelmingly covered in blood-red pigment, differing markedly from the torrent of colors and materials at play on the surface of Collection. Significantly, both Cherry-red Paintings remain very much paintings. By contrast, Collection conspicuously steps abroad from the painterly arroyo to surface construction that marks the Red Paintings and toward the open-minded, "come every bit you are" attitude to materials that is a defining characteristic of the Combines. The noteworthy differences between the early country of Drove and the Red Paintings are the palette of master colors, the college percentage of surfaces left unpainted, and the sculptural elements assembled on the surface and top border. In this first incarnation, then, Collection was arguably well on its fashion to being a Combine.

To be fair, the concurrent showing of Crimson Paintings and Combines at Egan Gallery is indicative of the fact that Rauschenberg's transition from one to the other was past no ways linear, and in fact the ii series were not considered past the creative person or observers to be divide entities until several years later.ten Decades of scholarship have produced a general chronology for Rauschenberg's creative development in the period 1953 to 1955, based on formal developments such as the introduction of additional colors and an increasing openness to leaving collage elements unpainted. However, the artist's habits of working on multiple pieces simultaneously and revisiting works that had been considered "finished" defy whatsoever endeavour to define a work-by-work progression. Perhaps nosotros should not exist surprised, then, that some art historians have considered Collection to be a Ruby Painting while others have alleged information technology the first full-blown Combine.11 Simply curator Walter Hopps's early on instinct that Drove marked new territory12 does seem to be confirmed by the nature of the changes that Rauschenberg wrought on the work shortly after the Egan showing.

Reworking Collection, Second State

4. Robert Rauschenberg, Carmine Painting, 1954. Oil and collage on canvas, 76 1/2 10 51 in. (194.3 x 130 cm). Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed past VAGA, New York, NY

5. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Red Painting), 1954. Oil, material, and newspaper on sail, 70 3/4 x 47 7/8 in. (179.vii x 121.vi cm). Eli and Edythe Fifty. Wide Collection; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

half-dozen. View of Robert Rauschenberg's Collection (1954/1955) with highlighting indicating alterations the creative person fabricated after the work was outset exhibited

After the Egan installation photo was taken, Rauschenberg significantly reworked the upper 2-thirds of Drove, adding many of its now-signature elements (fig. 6).xiii Writer and friend of the artist David Myers purchased the artwork direct from Rauschenberg in about 1955;xiv Rauschenberg presumably had finished his reworking before Myers took possession.fifteen The next extant photo—Rudy Burckhardt'due south photo for the Swedish journal Konstrevy 16 —dates from 1961, and here the surface appears every bit nosotros see it today. The upper annals has gained large swaths of cloth and paint, partially concealing elements such as the sheets of newspaper that had once been visible at the elevation of the centre console. Off-white fabric rectangles and a thin floral printed fabric take been layered over the upper regions, and each fabric addition has been finished off with a flourish of paint. Quick, brushy swirls of bluish and greyness summit the added textiles in the upper corners, and a distinctive thick line of red paint, possibly squeezed directly from the tube, meanders across the left and center panels. Finally, Rauschenberg has added the focal-signal swipe of drippy white that trails down the central panel.

The isolated swipe of dripping paint is a recurrent gesture in the artist's repertoire from 1954 on, and this type of mark has frequently been referred to in the Rauschenberg literature as a "hinge" stroke.17 The mark emerged in the Red Paintings, with its earliest incarnation being the short stroke of white floating off-center in the Weisman Reddish Painting of 1954, introduced above every bit figure iv. Throughout the Red Paintings and in Yoicks (1954), pigment becomes less and less a material with which to cover canvases and more a self-contained entity used self-consciously to reference Painting with a capital "P"—a transition much discussed in recent Rauschenberg literature. Regarding the white hinge stroke in Drove, Branden Due west. Joseph has written that Rauschenberg invented a new relationship betwixt painter and pigment stroke, in which brushstrokes sit atop the canvas "as quotations or allegorical appropriations of expressive gestures."xviii Similarly, Yve-Alain Bois discusses Rauschenberg'due south strategy of "leveling" materials, an approach that equates paint with all the other physical materials in the Combines: "There is no cardinal difference betwixt a collage element and a painted one. In his work, any atom—whether industrially, mechanically, or manually produced—is, as it were, in quotation marks."19 The iconic paint stroke would become on to appear in Combines such as Bed and Rebus (both 1955), and it would attain its full potential in Factum I and Factum Ii of 1957, a pair of nearly identical paintings that doubles down on the thought of the paint stroke in quotation marks, every bit the strokes in each painting finer cite those in the other. So used, pigment ceases to be Painting and becomes instead a declaration of non-painting, an indicator that these works are resolutely something else.

seven. Robert Rauschenberg, Yoicks, 1954. Oil, fabric, paper, and newsprint on two separately stretched canvases, 96 × 72 in. (243.8 × 182.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the artist; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

If the introduction of the white hinge stroke and the aforementioned red squeeze line to Collection exemplifies a new relationship between painter and paint stroke, the layered fabrics added to the upper sections of the work demonstrate a new, almost concurrent development in the artist's attitude toward collage. Many of the fabrics chosen for Drove appear in multiple artworks created between 1953 and 1956: Yoicks (1954, fig. 7), Charlene (1954), Interview (1955), Small Rebus (1956), and Honeysuckle (1956), as well as several untitled pieces. Equally noted past Walter Hopps, Yoicks offers the earliest example of Rauschenberg using the inherent patterns, colors, and textures of textiles as compositional elements.twenty Collection continues this strategy and goes a stride further, employing the textiles in the complex game of hide-and-seek that also is typical of the Combines. This strategy of the fractional reveal was initiated in the get-go state of Collection as overlapping sheets of newsprint and paint strokes of varying transparency that both invite and discourage attempts to read the surface. All the same, the push-pull dynamic reached a new level when the resolutely opaque swatches of textile were attached, calculation an nigh archaeological character to the work.

All the strategies that define the Combines visibly unfold in the post-Egan alterations to Collection: the every bit-is juxtaposition of found objects, the autonomous approach to materials, and the coaction of revealed versus concealed content and meaning. Hopps long agone identified the import of Collection in the earliest systematic scholarly consideration of Rauschenberg'south corpus, writing "it is probably the first piece of work in which Rauschenberg incorporated the full range of art-making techniques that have come to be associated with his combines."21 Nevertheless, what Hopps could not know was that the surface of this seminal work was an ongoing testing basis for the development of Rauschenberg'due south evolving artistic vocabulary.

American and European Exhibitions, 1963–1976

Collection remained largely out of circulation in the 8 years following the Egan exhibition; the artwork was not exhibited publicly and appeared simply once in print, as the above-mentioned illustration to a 1961 article by Öyvind Fahlström in Konstrevy.22 The next exhibition of Collection did non have place until 1963, when it was shown in Lawrence Alloway's Vi Painters and the Object at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.23 By that time, it had been sold to Ileana and Michael Sonnabend.24 (Although the Sonnabends took up permanent residence in Paris in late 1961, the artwork appears to have remained in New York until shortly later the Guggenheim exhibition ended.25) Ileana Sonnabend brought Collection across the Atlantic in late 1963 or early 1964 and placed it in six major European exhibitions betwixt 1964 and 1971,26 years that brought Rauschenberg widespread recognition and financial success. This period of international accomplishment was unprecedented for an American creative person, and information technology coincided with the upsurge of both the recognition of New York'south dominance of the international fine art scene and the value of American art more generally in the global marketplace.27 Circulating in high-contour European exhibitions and publications in these years, Collection played a significant role in the rising of Rauschenberg's reputation.

Sonnabend sold Collection to SFMOMA in 1972, and it made its way to the W Coast. The work was the first Rauschenberg SFMOMA acquired (Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson purchased information technology for the museum), and it has been on view at the museum nigh continuously since its arrival.28 Due to its fragility, Collection is lent merely in exceptional circumstances, as it was for the 1976 retrospective that Hopps organized for the National Collection of Fine Arts (NCFA; at present the Smithsonian American Fine art Museum). Soon before the 1976 testify, Drove received the name past which it is at present known. The work was one of a number of Combines that had remained untitled through the 1970s, and in grooming for the exhibition Hopps discussed with the artist the possibility of naming them. Rauschenberg was clearly open up to the change, and he later conveyed in the 1999 SFMOMA interview his distaste for untitled paintings, saying that it was "'Cause I like language so much."29 Hopps suggested that the choice of the proper name Collection was influenced past the venue, the National Drove of Fine Arts, only presumably information technology was also a reference to the collection of artwork reproductions gathered on its surface.30 NCFA officials notified SFMOMA of the championship change.31

The Mirror and Veil

Shortly after Collection'south arrival at SFMOMA in 1972, the piece of sheer silk material that had covered the modest mirror in the eye of the canvas was establish on the gallery floor. It is unclear how the fabric had detached from the artwork, though it appears that information technology had become brittle and subject to breakage simply due to age. SFMOMA conservators noted and preserved the found flake just chose not to reattach it at that time, as the fabric was too deteriorated. The mirror was left bare (fig. eight), and the artwork was exhibited and published this way for more than ii decades, including in the artist'south 1976 and 1997 retrospective catalogues.

On the occasion of SFMOMA's suite of Rauschenberg acquisitions in 1998, the artist visited the museum, and staff consulted with him regarding the status of the piece of work and the possible replacement of the silk. The artist then returned to his studio and dyed 2 pieces of fabric with a combination of powdered tea and 2 varieties of ruby-red wine to obtain the desired color. A new veil was made from the commencement piece of cloth and meticulously attached to the remaining frayed border on the surface. (The second piece of fabric was retained in SFMOMA's Artist Materials Annal in the upshot that information technology was needed in the hereafter.) Some fourteen years later, the color had again faded noticeably (a change due to the organic pigments of the tea and wine dye bath) and the edges of the adhesive had begun to lift. In 2012, the conservation squad decided to supersede the silk again, using the 1998 template but with a more colorfast fabric. Synthetic dyes were mixed to match the colour of the replacement veil to the reserved, unfaded 1998 swatch.

In retrospect, the conclusion to leave the mirror uncovered for more than twenty-five years seems perplexing, considering how central the veiled mirror is to the work'south presence and the viewer's experience of its surface. In a peekaboo, game-like style, the mirror reflects the room around it and offers united states of america a tantalizing, however ultimately frustrated, opportunity to glimpse ourselves through the veil. Rauschenberg discussed the use of mirrors as a style to counteract the stillness of a static finished painting,32 and mirrors do indeed appear in many of the major pieces he made betwixt 1949 and 1960. Since the piece of work'southward start showing at Egan Gallery, the veiled mirror has always been the most discussed aspect of Collection, beginning with Frank O'Hara'south oft-quoted review in ARTnews: "Lifting up a scrap of pinkish gauze you stare out of the moving picture into your own magnified eye. He provides a means past which you lot, as well as he, can become 'in' the painting."33 Getting "in" the painting requires, of form, that the work exist hung at a elevation that positions the mirror at eye level. The Egan photo shows Collection hanging perhaps twelve or thirteen inches from the flooring, which is much lower than is typical of a museum or gallery context. At such a height, the mirror sits direct at eye level.34

The mirror itself has grown cloudy over time, reflecting less and less of its environment and offering diminishing viewer interaction. The work'south overall colour has also changed considerably, with both the newsprint and the colored fabrics fading. After seeing the early on Combines in the 2005 exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Combines, Jasper Johns (whose firsthand knowledge of their original advent is unparalleled) noted that "the unfortunate thing about those early works is that they take on a quality of being relics. Originally, they were fresh, immediate, not precious—things apt to exist overlooked, picked upwardly hither and there, similar a minute agone."35 Early colour images of the artwork convey this freshness to the degree possible in a reproduction. Although Collection however feels vibrant and the layered elements retain some of that feeling of being swept up off the streets, the work has acquired a patina of age that is somewhat at odds with its original conception (fig. 9). The ephemeral nature of the materials Rauschenberg chose will go on to nowadays conservation likewise equally presentation challenges as the crumbling procedure transforms the experience viewers volition take of the artwork.

In 1956, Rauschenberg wrote of his works: "They are usually over-sized, bad-mannered, spontaneously synthetic and most of the materials used are fairly impermanent. Consequently, the finished work is either fragile or in need of repair. . . . I try to utilise these materials in such a way that they do non forfeit their identities for the sake of colour, form or texture. (They are these already.) In this way, I consider the text of a newspaper, the particular of a photograph, the stitch of a baseball and the filament in a low-cal bulb equally central to the painting as the brush stroke or enamel drip of paint."36 Swain artist and friend Dorothea Rockburne later remembered the debut of the Combines at the 1954–55 Egan Gallery exhibition and noted that "Everyone hated them. Even so, little by fiddling, people began to see in them a way out of the orthodoxies that then dominated the art world."37 Rauschenberg's fashion out was directly through his radically new approach to materials, an arroyo that he literally worked out on the surface of Drove.

Notes

- Recent texts referencing Collection include Yve-Alain Bois, "Center to the Ground," Artforum 44, no. vii (March 2006): 245–48, 317; Branden Westward. Joseph, Random Order: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Advanced (Cambridge, MA: MIT Printing, 2003), 72–119; Tom Folland, "Robert Rauschenberg's Queer Modernism: The Early Combines and Decoration," Art Bulletin 92, no. iv (Dec 2010): 348–65; Jonathan D. Katz, "'Committing the Perfect Crime': Sexuality, Assemblage, and the Postmodern Turn in American Fine art," Art Periodical 67, no. 1 (Leap 2008): 38–53; Jonathan D. Katz, "Jasper Johns' Aisle Oop: On Comic Strips and Camouflage," Queer Cultural Center, accessed August ane, 2011, https://www.queerculturalcenter.org/Pages/KatzPages/Katzoops.html; and Paul Schimmel, "Autobiography and Self-Portraiture in Rauschenberg'due south Combines," in Robert Rauschenberg: Combines, ed. Paul Schimmel (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005), 210–29. Though information technology does not specifically reference Collection, meet also Rosalind Krauss, "Perpetual Inventory," in Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, ed. Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 206–23.

- Drove was known as Untitled from its first showing in 1954–55 until 1976. See afterwards word in the primary text and notes 24 and 26 below.

- Rauschenberg continued to produce Combine paintings even after the stand up-lone works evolved. Untitled (1954, private collection, Paris), with an illuminated stained-glass panel across the height, is frequently referred to every bit the first Combine. Minutiae (1954, replica in drove of Walker Art Centre) was created as a set for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company's performance of the same name that opened in December 1954. Minutiae likely provided an impetus to explore the three-dimensional possibilities of the Combine form.

- The left panel includes a newspaper clipping dated August 22, 1954. Collection (and so known as Untitled) was dated 1954 in its first publication, in the Swedish journal Konstrevy. Öyvind Fahlström, "En gata full av presenter," Konstrevy 37, nos. v–six (1961): 176–81. In the 1963 catalogue for Six Painters and the Object, it was dated 1953–54. This 2nd dating held until Walter Hopps conducted research with the artist in preparation for the 1991 exhibition and catalogue Robert Rauschenberg: The Early on 1950s, at which bespeak the date was inverse to 1954. In lite of the changes made to Collection after the Egan Gallery exhibition closed in January 1955, the work has now been ascribed to 1954/1955.

- Robert Rauschenberg, video interview by David A. Ross, Walter Hopps, Gary Garrels, and Peter Samis, San Francisco Museum of Mod Art, May half dozen, 1999. Unpublished transcript at the SFMOMA Research Library and Archives, N 6537 .R27 A35 1999a, 54–55. This discussion occurs 2:15 min. into the video excerpt on Collection.

- The Egan Gallery exhibition is generally referred to in the literature equally Cherry-red Paintings and Combines, simply the scant extant documentation of this evidence refers to information technology simply by the artist's name. Come across Walter Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s (Houston: Menil Foundation and Houston Fine art Press, 1991), 167. No checklist exists for this exhibition; yet, two other snapshots of the exhibition taken past Rauschenberg show Yoicks (1954), Untitled (1954; no longer extant), and Untitled (Red Painting) (1954; Eli and Edythe 50. Broad Collection, Los Angeles); meet figure five. The floorboards, baseboards, and overhead beam in the snapshot of Drove correspond to known photos of Egan Gallery taken by the artist and held in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation archives. The paper and physical format also match these archival photos, confirming that this is a snapshot of the show. Encounter Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson, eds., Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 554.

- I wish to thank my colleague Paula De Cristofaro, paintings conservator at SFMOMA, for offering many insights during the extended period in which we studied the construction of Collection together. I also extend thanks and acquittance to my colleague Amanda Hunter Johnson, associate conservator at SFMOMA, who commencement noticed differences in the surface of Drove when we were reviewing photos at the Rauschenberg studio in May 2010.

- This painting has been dated ca. 1953 in previous publications, but a paper clipping embedded in the surface shows a engagement of May 23, 1954.

- Run into Rosalind Krauss's analysis of Rauschenberg's interplay of color and underlying materials in "Rauschenberg and the Materialized Image," Artforum 13, no. four (Dec 1974): 36–43; reprinted in Robert Rauschenberg, ed. Branden W. Joseph (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 39–55. Meet peculiarly 45–46.

- The exact date that the term Combine was coined is unclear, merely information technology was in apportionment by the time of Rauschenberg'due south next published review in January 1956. Leo Steinberg also used the term in his appraisal of the group exhibition at the Stable Gallery, "Month in Review, Contemporary Grouping at Stable Gallery," Arts Magazine xxx, no. four (Jan 1956): 46–47. Rauschenberg used the term himself in an unpublished Jan 1956 statement. Come across Catherine Craft, "In Need of Repair: The Early on Exhibition History of Robert Rauschenberg," Burlington Magazine 154, no. 1308 (March 2012): 191.

- Walter Hopps considered Collection to be an early on Combine. See Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, 164–68. Paul Schimmel also argues that Drove, Charlene, Pink Door (1954), and Blood-red Interior (1954) are early Combines in "Autobiography and Self-Portraiture in Rauschenberg's Combines," 214–16. In dissimilarity, Roni Feinstein classifies Collection and Charlene equally Red Paintings in "Random Guild: The First Fifteen Years of Robert Rauschenberg's Art, 1949–1964" (PhD diss., New York University, 1990), 165.

- Walter Hopps, ed., Robert Rauschenberg (Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1976), 77.

- Rauschenberg frequently revisited and contradistinct his works, sometimes many years after the initial date of completion. Every bit noted by Feinstein ("Random Order," 172), Charlene appears in the 1976 National Collection of Fine Arts catalogue in an earlier state. Rauschenberg is also known to accept continued altering and adding to his works long after they had been transferred to others' possession. Maybe the best-known instance of this is his 1985 repainting of a 1953 Black painting owned by John Muzzle, which had originally been a 1951 painted collage. Muzzle acquired the collage out of the 1951 Rauschenberg exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, and Rauschenberg shortly thereafter turned it into a Black painting, without Cage's consent. See Hopps, The Early 1950s, 172, plate 99. See besides Michael Kimmelman, "Robert Rauschenberg, American Artist, Dies at 82," New York Times, May xiv, 2008, accessed August 2, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/xiv/arts/design/14rauschenberg.html.

- The actual acquisition date is not recorded in whatever archival documents that have come up to light to date. Myers does not recall the specific date, but he is certain it was no later than 1958. David Myers, interview with the author, October 2011. Correspondence from Ileana Sonnabend incorrectly notes that Myers received it every bit a gift of the artist. See SFMOMA Permanent Drove Object Files: Collection, 72.26; letter of the alphabet from Ileana Sonnabend to Maryse Posenaer, Oct 29, 1983.

- The precise date of the reworking cannot be determined, though presumably the changes were made after the exhibition closed in January 1955. In conversation with the writer, Myers confirmed that Rauschenberg never reworked Collection while it was in his possession. The floral fabric in the upper left quadrant was used in other works created between 1954 and 1956, including Cherry-red Interior (1954), Interview and Monk (both 1955), and Honeysuckle, Rhyme, and Small Rebus (all 1956). This particular material does not announced in any works fabricated after 1956. Thus, the reworking must have taken place in 1955 or maybe 1956, though the later on appointment seems less likely, as Rauschenberg had moved on to unlike ideas and strategies.

- See notes iv and 22 for citation information and further word of the Konstrevy article.

- The term hinge stroke get-go appears in the literature, attributed to Jasper Johns, in Brian O'Doherty's "Rauschenberg and the Colloquial Glance," Fine art in America 61, no. 5 (September–October 1973): 82–87. Feinstein also notes that Johns may take been the first to denote this type of painted element as a hinge stroke. Feinstein, "Random Order," 156, 184n17.

- Joseph, Random Order, 110.

- Bois, "Middle to the Footing," 248.

- Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, 76.

- Ibid., 77.

- Fahlström, "En gata full av presenter," 181.

- Exhibition Checklist. Circa 1963. Six Painters and the Object. Exhibition records. A0003. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Archives, New York. Six Painters and the Object was the outset New York museum exhibition to grapple with the emergence of Pop art, and amongst the first to characterize Rauschenberg equally a forerunner to the motility. The Guggenheim exhibition ran March xiv–June 12, 1963, overlapping with the retrospective at The Jewish Museum, New York, March 31–May 8, 1963.

- The verbal date of transfer from Myers to Sonnabend cannot be determined. Sonnabend noted that she purchased the painting from Myers in 1959 or 1960 in an October 29, 1983, letter to Maryse Posenaer, now in the SFMOMA Permanent Collection Object Files: Collection, 72.26. Yet, the Rauschenberg studio archive records Sonnabend's buy every bit 1961 or 1962. In a July iv, 1958, telegram, Sonnabend asks Castelli, "DID YOU QUOTE Toll MYERS Movie?" The question suggests the outset of a negotiation for purchase. A later, handwritten memo by Leo Castelli with the annotation "before Ileana'southward difference Nov. 1961" divides up the Rauschenberg works amid "LC" and "Il" and "RR" [LC=Castelli, Il=Sonnabend, RR= Rauschenberg]. "Myers piece?" is listed under Sonnabend'due south proper noun. Because the work was even so untitled at this time, it is generally referred to in correspondence and notes as "Myers slice" or "Myers moving picture." Serial i: Correspondence, Box xx, Folder 16, Sonnabend, Ileana, 1961. Leo Castelli Gallery records, ca. 1880–2000, bulk 1957–1999. Archives of American Fine art. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. No further correspondence or receipts accept been found to document the actual date ownership was transferred. I suspect that Sonnabend purchased Collection former in 1959 or 1960 and that it was essentially mingled with the Castelli Gallery stock. And then, when she and Castelli divided the works in advance of her motility to Paris, she officially took sole possession of information technology. The cost of $900 written on the back of Collection reinforces the thought that it was in Sonnabend/Castelli's holdings earlier 1960. The $900 figure is entirely consequent with Castelli cost lists for like works by Rauschenberg in 1957–59; by 1960, works of this scale commanded prices between $2,000 and $5,000. Series 2: Administrative Files, Box 38, Folder 10, Cost Lists, 1957–63. Leo Castelli Gallery records, ca. 1880–2000, bulk 1957–1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Collection did not appear in Galerie Ileana Sonnabend'south Rauschenberg shows in Feb and March of 1963, instead existence lent to the Guggenheim's Vi Painters exhibition. The loan documents from the Guggenheim went to Sonnabend care of Castelli at the Leo Castelli Gallery, so certainly by then her ownership was clear. Series ii: Authoritative Files, Box 34, Binder five, Loans Completed 1963–1964. Leo Castelli Gallery Records, ca. 1880–2000, bulk 1957–1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- The October 29, 1983, letter from Sonnabend to Posenaer cited in note 24, in a higher place, states that Galerie Ileana Sonnabend showed Collection in 1964 before the Venice Biennale. However, the only Rauschenberg prove at Sonnabend in 1964 earlier the May biennale opening conflicts with a confirmed London showing of Collection at the Tate Gallery in Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, 1954–1964, Apr 22–June 28, 1964. I believe Collection was shown at Sonnabend's gallery later in the year in Robert Rauschenberg: Untitled 1953–54 and Thirty-Iv Dante Drawings, December 1964–Jan 13, 1965. Offset date unknown. As noted previously, the piece was referred to as Untitled and dated 1953–54 as of 1964; information technology also was the only work carrying that title and date significant enough to build this Sonnabend exhibition around. Information technology is unclear what remains of records from the Sonnabend Gallery in this era. The 1983 letter also states that Collection was shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1964, which is non truthful but has been incorrectly published previously by SFMOMA. See the exhibition history on the artwork overview page for a consummate history.

- For the most thorough and intelligent consideration of Rauschenberg's role in the rise of American fine art in Europe, see chapters 1 and 2 in Hiroko Ikegami's The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 17–101.

- Since the 1992 acquisition of the Anderson Collection of Popular Art, the museum has contractually agreed to show Collection in a dedicated Anderson Gallery, a permanent installation of works from this significant gift.

- Rauschenberg, interview with Ross, Hopps, et al., May half dozen, 1999, 53.

- Ibid., 52–54.

- Neil Printz, National Collection of Fine Arts, letter to Karen Tsujimoto, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, July 26, 1976. SFMOMA Permanent Drove Object Files: Collection: 72.26.

- "Robert Rauschenberg," in Record of Interviews with Artists Participating in the Popular Image Exhibition (Washington, D.C.: Washington Gallery of Mod Art, 1963), 45.

- Frank O'Hara, "Bob Rauschenberg," ARTnews 53, no. ix (January 1955): 47. Interestingly, O'Hara's choice of words echoes László Moholy-Nagy'due south ideas on reflectivity as the logical endpoint of modernist painting. For a compelling assessment of John Muzzle'due south distillation of Moholy-Nagy as evidenced in Muzzle's response to Rauschenberg'south White Paintings, see Joseph, Random Society, 33–42.

- With the lower edge at twelve to thirteen inches from the floor, the midline of the artwork would exist at l-ii or fifty-three inches, extremely low in a museum context. SFMOMA typically hangs paintings of this size on a sixty-inch midline, which would identify the mirror several inches higher up heart level for most viewers. At twelve inches from the floor, the mirror would be at middle level. David White has noted the creative person'due south general preference for lower hanging heights. "SFMOMA 75th Anniversary: David White," interview conducted by Richard Cándida Smith, Sarah Roberts, Peter Samis, and Jill Sterrett, 2009, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 73–74. Accessed August ii, 2011, https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/roho/ucb/text/white_david.pdf.

- Jasper Johns, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, Lives of the Artists (New York: Henry Holt, 2008), 184.

- January 1956 statement by Rauschenberg quoted on untitled, undated typescript information sail on Rauschenberg in Castelli Gallery papers. Series 2: Administrative Files, Box 38, Binder 26, Rauschenberg, Robert–Writings, ca. 1956–1961, Leo Castelli Gallery records, ca. 1880–2000, bulk 1957–1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Dorothea Rockburne and Nan Rosenthal, "Tribute to Robert Rauschenberg," The Brooklyn Rails, June 2008. Accessed August 12, 2011, https://www.brooklynrail.org/2008/06/fine art/tribute-to-robert-rauschenberg-19252008.

Download PDF

cite as: , "Collection," Rauschenberg Inquiry Projection, July 2013. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/collection/

gonzalestworaverefor.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/collection/

0 Response to "Museum of Modern Art San Francisco Wall Section Museum of Modern Art San Francisco Section Drawing"

Postar um comentário