Five Phases in the Quality Improvement (Qi) Process

Who doesn't want to provide their clients and customers with the best products and services? All businesses want to improve the quality of their offerings, but not everyone has the same idea of what constitutes the best or the highest quality. And people differ on how to achieve such aims. Especially in fields like healthcare and education, where evaluations often rely on results rather than tallies, a formal quality improvement (QI) process can be essential.

In this article, we will explore quality improvement processes in fields such as healthcare and education, uncover the must-haves in a good QI plan, and study the methods and tools to pursue a strong strategy. You'll also find links to templates and best practices from a QI expert.

What Is Quality Improvement?

Quality improvement is a structured approach to evaluating the performance of systems and processes, then determining needed improvements in both functional and operational areas. Successful efforts rely on the routine collection and analysis of data. A quality improvement plan describes an ongoing, or continuous, process through which an organization's stakeholders can monitor and evaluate initiatives and results.

Based on the thinking of such experts as W. Edward Demings, QI principles were developed in manufacturing in the 1940s. In the last two decades, QI processes have also become popular in healthcare and education.

Although organizations take many approaches, QI at its foundation concerns process management. If organizations operate according to many processes, by reviewing and improving one process at a time and leveraging the Pareto principle, they can more easily and gradually improve their entire system.

Quality improvement processes share these characteristics:

-

Quality improvement is data driven and regards the quantitative approach as the only reliable means to influence the qualitative elements. This principle is expressed in the following saying of quality improvement guru W. Edwards Deming: "The right data in the right format in the right hands at the right time."

-

QI focuses on processes, not people. In other words, the individual is never at fault.

-

QI involves people as part of the improvement solution and looks for what is attributed to Deming as "the smart cogs," the employees who are directly involved in and best understand the processes in an organization.

See how Smartsheet can help you be more effective

Watch the demo to see how you can more effectively manage your team, projects, and processes with real-time work management in Smartsheet.

Watch a free demo

What Is the Main Purpose of Quality Improvement?

Quality improvement aims to create efficiencies and address the needs of customers. In healthcare, the main purpose of quality improvement is to improve outcomes. In healthcare settings, quality improvement may be associated with continuous quality improvement, the method used to identify problems and implement, monitor, and provide corrective action.

The Benefits of a Quality Improvement Process

A quality improvement process can offer organizations the following benefits:

-

Solutions that focus on failures in processes, not flaws in people

-

A reliance on objective, data-driven solutions, rather than subjective opinions, to identify inefficiencies, preventable errors, and inadequate processes

-

Improvements that provide better customer service, increased efficiency, greater safety, and higher revenues

-

A localized focus on testing small, incremental improvements that is less risky than a focus on making changes at one time

-

Data collection to monitor improvement efforts, which can provide the basis for reimbursement and certification programs, particularly in healthcare organizations

Primary Issues in Quality Improvement

Quality improvement plans are frequently measured in terms of results, employee and stakeholder satisfaction, ease of change, and cost. Quality improvement plans must also help companies understand how to meet the needs of diverse stakeholders (employees, customers, regulators, and others), find a method for prioritizing the improvement requirements of these stakeholders, comprehend the threshold of variation that will permit required change, and know how employees can succeed in a program if leadership support is inadequate.

Why Don't People Believe in Quality Improvement Processes?

Who could fault an effort to make work more efficient or effective or to deliver higher-quality output to internal and external customers? No one, you would assume — yet employees often shudder at the mention of quality improvement efforts. Their suspicions have assorted origins:

-

Organizations don't back change efforts with human resources and other shows of support, then express surprised disappointment when nothing improves.

-

Employees have previous experiences with efforts that produced no improvements.

-

Employees feel that "they're coming after you." They picture a punitive focus on the individual, rather than an effort to fix the process.

-

People who value action find data collection and analysis tiresome.

Natenstedt notes, "The CFO, when they're sending out a memo, assumes everybody is reading it. But if your team communicates exclusively by corkboard, how're you supposed to know what decisions have been made and how they affect you?"

Difficulties in Pursuing a Quality Improvement Process Plan

Here are some of the common difficulties in following through with a QI plan:

-

Expectations are not clear.

-

Leadership is not adequately engaged, making bottom-up initiatives difficult.

-

There is insufficient time and resources to properly implement the initiative.

-

In healthcare settings, some physicians don't implement new systems until they have confidence in new processes.

-

There is an inadequate emphasis on the importance and use of new measures.

-

There is a poor level of collaboration between teams.

-

People underestimate the time required to implement a program.

-

The extent to which a result depends on a change can't be measured because the extent of the original problem has not been measured.

-

Specific improvement cycles can't be evaluated.

-

Costs can't be evaluated.

-

Changes result from the Hawthorne effect rather than the QI program. In this interpretation of the Hawthorne effect, stakeholder behavior changes because their activities and results are monitored.

-

A small sample size makes generalizations impossible.

-

Solving some problems creates additional problems.

-

Targets are overly ambitious and therefore difficult to achieve.

-

There are too many diverse stakeholder conditions.

How to Succeed with a Quality Improvement Process Plan

According to Natenstedt, every successful QI plan needs a champion: "The most important factor contributing to successful implementation is highly committed senior leadership. For any quality improvement process, you need that leader who wants to make it happen. Success comes because someone at the top is pushing for it."

In addition, Natenstedt says that QI projects flourish when stakeholders are invested in the outcome. "The projects that tend to go the best also tend to be the ones that tie back to the main mission of the organization," he explains. "If you're trying to get traffic to flow better in the parking garage, nobody's committed. But if you're reducing infections, every employee gets involved, because people care about the quality of what they're providing.

"That's when leadership has the crucial job of getting everybody on board. They accomplish this goal by explaining exactly why this particular solution is important and showing precisely who reaps the benefits," Natenstedt continues.

Leadership for QI initiatives may be separate from the organizational structure and should best suit your particular system. In any case, leadership provides the needed resources, as well as the direction and support for core values and priorities. Because leadership is essential, it's crucial to report any successes and obstacles back to them.

In addition to leadership, Natenstedt says teams need time, space, and opportunities to talk. "The primary team and other teams who will have great insights need collaborative, open, free thinking time. You have to get in a room, spend some time together, and not be afraid, no matter what you have to say or who you're saying it to — a no-stupid-ideas environment," he adds.

Natenstedt emphasizes that different perspectives are essential: "Make sure the team is not dominated by one type of person or employee. Get a diverse range of voices — even clients' opinions. That fosters creative exchange."

Other characteristics that contribute to a successful QI initiative include the following:

-

Offer consistent and continuous commitment.

-

Secure funds and other resources to support the plan.

-

Create a vision for quality by using shared goals within and across teams. Engage all stakeholders to help define priorities for safety or cost savings. Take a multidisciplinary approach that includes peers from all teams, as well as frontline workers who implement and champion changes.

-

Develop and agree on a plan for how to implement improvement activities, who will lead them, and how they will start.

-

Build a quality improvement team. Work with that team to prioritize and implement improvements.

-

Spread the word about initiatives and successes. Use one-on-one opportunities, newsletters, and other channels to discuss wins. Openly discuss successes and failures.

-

Publicize the successes. Stories of success build motivation. Encourage people to talk regularly about quality and contribute suggestions.

-

Educate stakeholders to prepare for initiatives by scheduling ongoing training and weekly meetings, especially with teams that have no previous experience with QI programs. Provide staff with the training and tools they need to measure and improve efforts. Seek outside support if necessary.

-

Educate stakeholders on the subject area of the initiative.

-

Collect the right data — however difficult — and use it well.

-

Measure progress regularly.

-

Use current resources as much as possible.

-

Identify incentives that help members of an organization appreciate and cultivate change. Incentives may be financial or nonfinancial. Think about reducing errors, improving communication, and diffusing tension.

-

Find influencers (i.e., people who others in the organization respect), and leverage that influence to spread ideas about change. Most people do not conduct research; they simply listen to the opinions of others.

-

Establish realistic goals. Don't aim for 100 percent success.

-

Find an approach to metrics and documentation that suits your organization. "Within any project, you need a meaningful set of KPI (key performance indicators) that you can measure before and after," says Natenstedt. "The old adage of 'what gets measured gets improved' is 100 percent true. And people will respond to the measurement simply because a measurement is being taken."

-

Create a robust IT implementation to record data, changes, and plans, as well as to leverage electronic health records (EHRs) and public databases where appropriate.

-

Involve customers through surveys, exit interviews, and suggestion boxes. This information generates valuable ideas based on clients' direct experiences with your services. In return, find user-friendly ways to help customers understand data.

Common Outcomes of Successful Quality Improvement Process Projects

Many organizations have found the following successes with QI:

-

Standardization eliminates the need for individual decision making.

-

By limiting options and changes, information technology (IT) forces functions that reduce errors. For example, IT eliminates redundant checks and barcodes by using computer-aided calculations.

-

When a culture encourages teams to report errors and near misses, they generate data that creates a foundation for understanding root causes.

A Case Study in Quality Improvement Process Implementation

As an example of what can go right and wrong in a QI plan, Carl Natenstedt tells the story of his company's plan to remove and reallocate old product to save a hospital tens of thousands of dollars. "But those benefits weren't communicated to the clinicians who actually used the product every day," he explains.

"When the time came for our team to come into the hospital and remove medical supplies, we were met with resistance. Nurses and doctors were worried about running out of what they needed, which is totally understandable. No one had presented them with the numbers or communicated with them. No one had said, 'You actually don't need these eight extra boxes of sutures. We know because we've analyzed your usage history. You could reduce your patients' cost of care by X amount,'" he notes.

Resistance continued until senior leadership explained the benefits. "As soon as you quantify just how much you're helping your community, people are interested. They're excited," Natenstedt says.

What Is the First Step in the Quality Improvement Process?

No matter which model you choose or what you call it, planning has to be the first step. You need to decide what problems you want to solve, how you will solve them, and how you'll know when they are solved.

What Is a Quality Improvement Plan?

A quality improvement plan is the written, long-term commitment to a specific change and may even chart strategic improvement for an organization. A QI plan defines what your organization wants to improve, how it will make improvements, how it will test for success, and what are the anticipated outcomes and evidence of success. In essence, the plan becomes the monitoring and evaluation tool. Additionally, a QI plan provides the roadmap and outlines deliverables for grants, funding, or certification applications.

A plan differs from a QI project or QI program, both of which are considered subcategories of a plan. Projects grow out of the target areas you identify in the plan or those noted by stakeholders. With regular monitoring of changes, you can spotlight further targets for improvement.

Ensure that your quality improvement plans include the following elements:

-

Clearly defined leadership and accountability, as well as dedicated resources

-

Specified data and measurable results that suit your goals

-

Evidence-based benchmarks. In an evidence-based practice, teams determine the clinical or operational approaches that most often produce good outcomes, then create procedures to consistently implement those approaches. In benchmarking, employees learn about processes and results at comparable organizations. Then they consider how to implement similar processes in their own organization.

-

A mechanism for ensuring that you feed the data you collect back into the process. By doing so, you guarantee that you accomplish your goals. It also helps ensure that these goals are concurrent with improved outcome.

-

More than one QI method or tool

-

A built-in structure to keep the plan dynamic and ongoing

-

Attentive staff members who listen to the needs of all stakeholders

-

In healthcare, steps and measures that align with other quality assurance and quality improvement programs, such as those sponsored by Medicaid and HRSA

What Steps Are in the Quality Improvement Model?

Regardless of the framework you choose, the following six steps generally describe all quality improvement approaches:

-

Create a mission statement and vision statement to provide the organization with strategic direction.

-

Create improvement goals and objectives that provide quantitative indicators of progress, which can help to show areas of quality needs.

-

Analyze the background and context of the issues. Research and develop possible strategies to resolve the issue.

-

Choose specific interventions to implement.

-

Focus first on change in small and local structures. Test implementations to refine ideas and make change palatable to the individuals involved. You can scale successful plans to the larger organization.

-

Define a performance measurement method for your improvement project, and use existing data or collect data that you will use to monitor your successes.

-

-

Plan data collection and analysis.

-

Data is imperative to a QI project. Measure input, outcomes, and processes. Data management includes collecting, tracking, analyzing, interpreting, and acting on data.

-

Leadership and stakeholders usually review goals on an annual basis, but you should collect data more frequently.

-

No collection frequency works for all organizations, but you should specify the rate in your plan.

-

Charge one person or department with the responsibility of managing data. That way, if the designated staff member changes positions, it's easy to locate and shift ownership.

-

Analyze and interpret data to identify opportunities for improvement. Analysis determines if data is appropriate, and interpretation identifies patterns.

-

Establish an improvement team.

-

Prepare the written QI plan.

-

-

Based on the plan, make changes to improve care, and continually measure whether those changes produce the improvements in service delivery that you wish to achieve.

-

Communicate successes to keep quality on the agenda.

Quality Improvement Tools and Frameworks

Quality improvement methods provide frameworks for pursuing change. Quality improvement tools provide strategies and documentation to gather and analyze data, as well as communicate results and conclusions.

The History of Quality Improvement

Most modern quality improvement approaches trace their history to modern efficiency experts, such as Walter Shewhart, who perfected statistical process control modelling. Other foundational methodologies include the Toyota Production System, which evolved into lean management. W. Edwards Deming heavily influenced both the former and the latter.

In healthcare, beginning in the 1960s, the Donabedian model became globally influential. Developed by Avedis Donabedian at the University of Michigan, the approach examines structure, process, and outcomes to inquire into the quality of care. Subsequently, healthcare organizations began to turn to frameworks used in other fields. Here are the most prominent of those additional frameworks:

-

Total Quality Improvement (TQM): The TQM model is an approach involving organizational management, teamwork, defined processes, systems thinking, and change to create an environment for improvement. TQM espouses the view that the entire organization must be committed to quality and improvement to achieve the best results.

-

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI): The CQI process is designed to introduce frequent, small reviews and changes, and it operates on the principle that opportunities for improvement exist throughout the practice or institution. Popular in healthcare, CQI is used to develop clinical practices and has recently found traction in higher education. CQI incorporates QI methods such as PDSA (plan-do-study-act), lean, Six Sigma, and Baldrige. In healthcare in particular, CQI adopts/operates the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement.

-

Clinical Process Improvement (CPI): CPI is a clinician-driven approach to addressing the many challenges and complexities that exist for modern healthcare providers. In CPI, teams follow the four QI steps: find a goal; gather data; assess data; and implement changes.

Commonly Recognized Quality Improvement Methods

Organizations choose methods based on their specific improvement goals. Each method offers varying advantages, depending on the company's particular scenarios and environments:

-

Rapid-Cycle Quality Improvement: This method allows for quick integration of changes over short cycles.

-

ISO 9000: The ISO 9001 standard of the ISO 9000 series is a framework that embraces continual improvement and certifies that an organization has an industry-recognized plan for pursuing quality.

-

Six Sigma: Six Sigma is a data-driven framework to eliminate waste. Using the DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) model, Six Sigma teams define a project or problem, review or measure historical experiences, analyze results, and decide on solutions that reduce variability in outcome. Teams then implement solutions and control or regularly monitor statistical output to ensure consistency. Six Sigma is closely related to PDSA, as it is based on Shewhart's PDCA (plan-do-check-act).

-

Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award: This is an improvement criteria named for quality guru Malcolm Baldrige, a contemporary of Deming.

-

Toyota Production System or Lean Production: This approach emphasizes the elimination of waste or non-value-added processes. In healthcare, it's used for process improvement in labs and pharmacies.

-

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA): This process improvement framework is fundamental to continual improvement and frequently provides steps for quality improvement in healthcare. PDSA, also known as the trial-and-learning cycle, promotes small changes and rapid adaptations and improvements. As such, it is suited to organizations that contain many units and processes that interact and yet often function independently. Within such companies, small, incremental adjustments can eventually have significant impact on the entire system.

-

5S or Everything in Its Place: This set of principles aims to make the workplace safe and efficient. 5S stands for the following Japanese terms and their English translations: seiton, set in order; seiri, sort; seiso, shine; seiketsu, standardize; and shitsuke, sustain. For further information on this topic, please see "Everything You Need to Know About Lean Six Sigma."

-

Human Factors (HFE): HFE studies human capabilities and limitations and how they apply to the design of products, tools, and processes. HFE has a strong track record of success in improving manufacturing processes and is now proving helpful in clinical applications to bolster quality, reliability, and safety.

-

Zero Defects: This industrial management strategy centers on reducing and eliminating defects through a continuous focus on punctual and accurate performance. In the United States, this strategy was highly popular in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Quality Improvement Tools

The following tools work in conjunction with the quality improvement methodologies mentioned above:

-

Root Cause Analysis (RCA): This is a way of looking at unexpected events and outcomes to determine the underlying causes and to recommend changes that are likely to fix the resultant problems and avoid similar problems in the future.

-

RCA Tools: RCA tools include the five whys, appreciation or situational analysis ("so what?"), and drilldowns. These tools reveal finer details of a larger picture, such as state-by-state data emerging from national data and fishbone diagram subprocesses emerging from general processes. In healthcare, RCA is applied after sentinel events, which are unanticipated events that result in death or serious physical or psychological injury to one or more patients in a clinical or healthcare setting. By definition, these events are not caused by a pre-existing illness.

-

-

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA): This is a systematic approach to identifying what could go wrong. Before an event, you apply FMEA to consider all adverse outcomes and mitigate these possibilities. Ideally, this mitigation process would take place both during the design phase and later, during implementation. The FMEA process addresses these questions:

-

Failure Modes: What could go wrong?

-

Failure Causes: Why could this happen?

-

Failure Effects: What would be the consequences of this failure?

-

Health Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (HFMEA): The U.S. Veterans Administration National Center for Patient Safety created the HFMEA for the purpose of risk assessment. Application of the tool includes identifying failure modes, then applying a hazard matrix score.

Statistical Process Control for Quality Improvement

Statistical process control (SPC), which measures and controls quality, started in manufacturing, but can apply in a range of other fields. SPC relies on the continuous collection of product and process measurements, as well as the subsequent subjection of said data to statistical analysis. In manufacturing, you collect data from machines in the production line. You can even compare data of different sizes and characteristics. For example, in Statistics and Data Analysis in Geology, John C. Davis writes, "In order to compare resultants from samples of different sizes, they must be converted into a standardized form. This is done simply by dividing the coordinates of the resultant by the number of observations, n…"

PDSA for Quality Improvement

The PDSA cycle of plan-do-study-act offers a common framework for improvement in healthcare, education, industry, and other areas. PDSA may take several cycles to test and perfect, but the cycles of implementation also disseminate ideas. The framework scales from small to large organizations.

At its core, PDSA maps to these active, iterative learning steps:

-

Ask:

-

What do you want to do?

-

How will you know that a change has created an improvement?

-

What changes will create improvements?

-

-

Then:

-

Develop the plan.

-

Implement the changes.

-

Verify the results.

-

-

Make additional improvements.

The PDSA cycle can have three implementation expressions. The healthcare industry uses rapid-cycle problem solving, usability testing, and practice-policy communication loops; educational organizations use practice-policy communication loops. The three implementation expressions operate as follows:

-

Rapid-Cycle Problem Solving: This encourages teams to plan changes and make updates within three months, rather than within eight to 12 months. This approach is suited to electronic health record implementations and where fast improvements can make a big impact on stakeholders.

-

Usability Testing: With origins in software development, usability testing offers iterative testing with various small groups. The ideal series of tests is four to five, with different groups of four to five people. Each test reveals unique roadblocks and errors, usually starting with superficial problems and culminating in more fundamental issues. As you implement improvements, you may introduce new problems that require fixes.

-

Practice-Policy Communication Cycles: The practice-policy communication cycle model was articulated to explain how complex products and processes, such as legacy software systems, and organizations could discover where and how to make improvements. In this bottom-up approach, grassroots (or practice) levels maintain regular communication with management and top-tier (or policy) levels about requirements and changes. This ensures that the relevant party records improvements in the form of policy.

PDSA steps capture the following activities:

- Plan: The planning phase involves establishing goals, choosing areas of focus, identifying improvement strategies, and preparing the QI plan.

- Establish Goals: What do you want to improve? Review may be infrequent, so consider setting SMART objectives to act as interim progress indicators that contribute to the major goal. To set goals and objectives, answer these questions:

-

What does your organization or team want to accomplish?

-

Where do you need to improve service or care?

-

What about a workday or customer experience is most frustrating to employees and customers or clients?

-

Where can you be more efficient?

-

- Create an Initiative Team: Include representatives from a group or team affected by change, but consider including both functional and operational representatives. Include special team members as necessary. Some sources suggest that a team with a maximum of 10 members is the most effective. Establish an implementation and review the timeline for the initiative.

-

Determine Solutions: Solutions must fit the problem, align with the culture of the organization and the clients it serves, or provide technological upgrades or advancements. Here are some options for finding possible solutions:

-

Visit other facilities. Seeing what others do can help the team overcome internal resistance to change.

-

Glean information from conferences, subject-area literature, and academic literature.

-

Find benchmark practices for your speciality.

-

Talk to your clients. For example, in healthcare, survey your patients and their families.

-

-

Prepare the Plan: Add strategies and sub-strategies. Include answers to these questions:

-

What are the goals?

-

What are the objectives?

-

What areas do you want to improve?

-

What actions can accomplish these goals?

-

Which stakeholders will be affected and how?

-

Who can lead or champion the initiative?

-

What resources do you need: budgetary, human, or material?

-

What are the potential barriers? How can you overcome them?

-

How will you measure improvements and successes? Describe the benchmarks that will monitor progress in achieving objectives and goals. In clinical and other healthcare organizations, find metrics to determine whether team members adhere to new or revised practices. Do this to understand how practices influence patient care and to ascertain whether care is improving and to what extent.

-

What is the timeline?

-

How will you share your action plan?

-

-

Do: Implement the plan in short cycles and localized areas, executing small adjustments and evaluating changes on qualitative and quantitative bases. At this stage, you also collect data. Your plan should already indicate measurements that will provide the most impact and that will not pose a burden to staff and stakeholders. Ensure that you explain to the entire team why you are collecting data. Frame data collection as the attempt to learn what works. Teams will be more enthusiastic about making changes and collecting data when they are focused on the positive, rather than on finding problems and mistakes. Also, keep in mind that while data can highlight change over time, data and charts in and of themselves do not necessarily point to best practices.

-

Data is often best gathered in documents such as check sheets, flowcharts, swimlane maps, or run charts, which can also help with displaying and sharing data:

- Check Sheet: Also called a defect concentration diagram, a check sheet is adaptable to different situations. It is a structured form for collecting quantitative and qualitative data. Check sheets are among the seven basic quality tools.

- Swimlane Maps: Also known as deployment maps or cross-functional charts, swimlane maps describe processes according to functions, which are displayed in the lanes.

- Flowcharts: Flowcharts graphically describe processes.

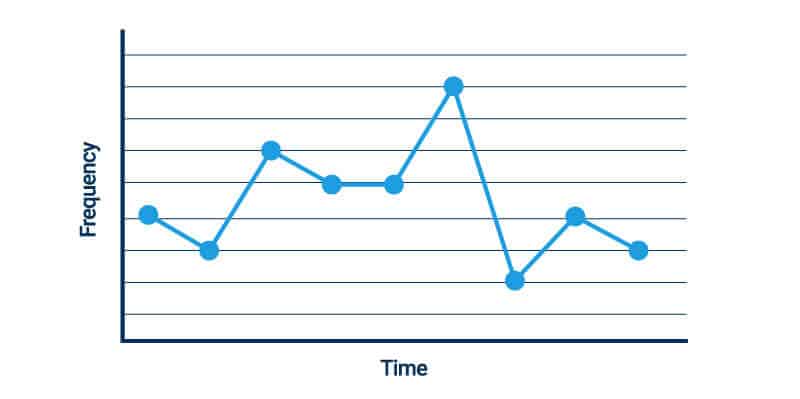

- Run Charts: Run charts use a single line to depict how trends in processes change over time, with upward and downward movement.

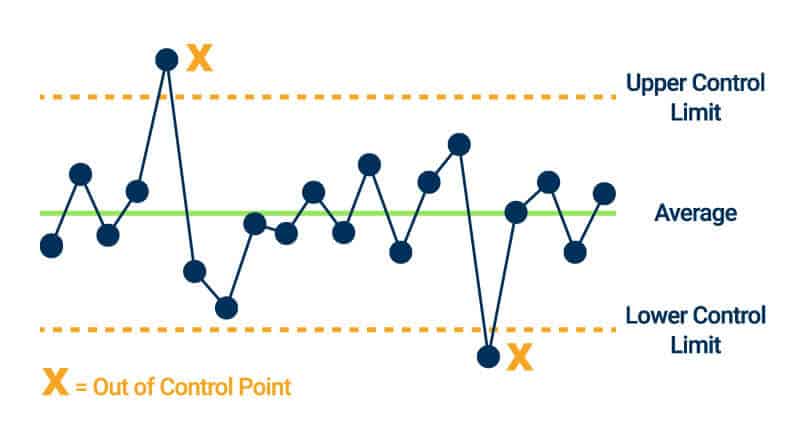

- Control Charts: Control charts plot changes in data with a single line. However, control charts include upper and lower control limit lines and a centerline. If data points exceed the limit lines, you know that your process is not stable; it is out of control. You can use control charts for internal benchmarking.

-

-

Study: Use collected data to determine what works and what doesn't work. Use run charts, control charts, and Pareto charts to visualize results. Share the results, especially the successes, to create enthusiasm through word of mouth. Don't be troubled by what appear to be failures. Because localized changes are not applied to the entire organization, you can easily make and roll out incremental modifications (when perfected) to the rest of the organization.

-

Act: When the plan succeeds, extend the steps to the larger organization. Adapt processes as necessary. Monitor results by month or by quarter. Identify and manage any barriers to adoption, such as:

- Fear of change, fear of failure, or fear of loss of control

- Grief over the loss of familiar practices or people

- Lack of basic management expertise

- Inadequate staffing levels

- Inadequate information technology systems

- Lack of training in functional and operational jobs

- Outdated or unreasonable policies

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Healthcare?

With its life-and-death focus, healthcare is a prime field for quality improvement initiatives. You can use QI processes for enterprises, clinics, labs, and individual practices. In healthcare, goals and objectives may be functional or operational, and they may include process measures and outcome measures. For example, you may improve your front-desk admissions process or your wound-care process. In healthcare, we measure improvements in terms of desired outcomes.

As this professional journal article states, "Evidence for variable performance of colonoscopy indicates that patient outcomes could be improved by a constructive process of continuous quality improvement." In this specific context of improving the performance of colonoscopies, this journal notes further that professionals can implement quality improvement by "educating endoscopists in optimal colonoscopic techniques, procedure documentation, interpretation of pathological findings, and scheduling of appropriate follow-up examinations." Pathologists can improve their work through the "appropriate reporting of pathological findings. Continuous quality improvement is an integral part of a colonoscopy program."

STEEP: A Quality Improvement Process in Healthcare

STEEP is a quality improvement tool unique to healthcare. Developed in 1999 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now the National Academy of Medicine, it is similar to FMEA and describes six goals for optimal patient care and safety:

-

Safety: Avoid injury to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

-

Timeliness: Reduce waits and harmful delays.

-

Effectiveness: Provide services, based on scientific knowledge, to all who could benefit — that is, avoid overuse. Refrain from providing services to those not likely to benefit — that is, avoid underuse.

-

Efficiency: Avoid waste.

-

Equitability: Provide care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, geographical location, and socioeconomic status.

-

Patient Centeredness: Provide care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.

In addition to general challenges inherent in pursuing quality improvement, healthcare presents particular obstacles. For example, healthcare organizations face a likelihood of adverse events recurring, and they must anticipate overcoming resistance to change among key parties such as physicians, as much as 16 percent of whom may be unwilling to revise processes.

Nevertheless, QI cycles and data capture support applications for financial programs. In addition, certifications provide measures to contribute to public reporting schemes and offer data to support value-based payment models.

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Nursing?

In nursing, the quality improvement process purports that the floor nurse is best situated to monitor the status of processes and make improvements. QI efforts from nurses can include safety issues (such as preventing patient falls), clinical issues (such as wound care and surgical procedures), and self-care for maintaining practitioner safety, health, and mental well-being.

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Education?

Continuous quality improvement is the framework for consistent improvement in education, both in higher education and in K-12 in public education. Although common in manufacturing and healthcare, quality improvement methods for education are now beginning to blossom. Methodologies in education include Six Sigma, PDSA, PDCA (plan-do-check-act), and in a few cases, lean.

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Information Systems?

Because they support data collection and analysis, information systems are key to the quality improvement processes of many types of organizations, especially healthcare. IT in healthcare leverages electronic health records (EHR) and health information exchanges (HIE), in addition to in-house data sources. Information systems can assist with such quality enhancements as generating patient reminders for screenings and preventive health checkups, as well as providing access to laboratory, radiology, hospital, and specialist reports and records.

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Software?

Software quality management (SQM) is a management process that aims to develop and manage the quality of software to best ensure the product meets the standards expected by the customer. At the same time, it also meets regulatory and developer requirements.

What Is a Quality Improvement Process in Supply?

In terms of supply, quality improvement focuses on mutual objectives across the supply chain, rather than on competition between suppliers. QI in supply commonly adheres to Baldrige National Quality Award 2002 criteria, which emphasizes the needs of the end-customer, not just those of the next customer in chain. Some examples include the idea, expounded upon by Evan L. Porteus in "Optimal Lot Sizing, Process Quality Improvement, and Setup Cost Reduction," that smaller lots provide less opportunity for defects and errors.

Build Powerful Quality Improvement Processes and Workflows with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there's no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Five Phases in the Quality Improvement (Qi) Process

Source: https://www.smartsheet.com/quality-improvement-process

0 Response to "Five Phases in the Quality Improvement (Qi) Process"

Postar um comentário